“Who Cares About Signature Blocks Anyway?” District of Kansas, Apparently.

I was listening to the latest episode of the legal podcast Advisory Opinions, “Must and May,” which covers a variety of topics, including a minor discussion about signature blocks. A comment caught my attention because of its relevance to generative AI misuse.

Advisory Opinions briefly discussed an Eastern District of Virginia District Judge asking “Lindsay Halligan why she continues to use the title in her signature block, ‘United States Attorney,’ after another judge in the district dismissed” indictments because she was not properly appointed. Ep. “Must and May,” Jan. 15, 2026

What caught my attention was this comment by David French:

It's a silly dispute in some ways—a silly dispute in a lot of ways—irrelevant to the merits. But I think it's quite clear that the administration's language was ridiculously aggressive. It also might be the case that the judge is being a bit...what would be the word that my dad would use? “Persnickety”, a little bit nitpicky, perhaps. I don't know. Who cares about signature blocks anyway? [empahsis added]

AO’s Mata v. Avianca Coverage

As I noted in my post about the Mata v. Avianca case, Advisory Opinions had some of the best contemporaneous coverage of that case. They did not just focus on the “ChatGPT made up fake cases” narrative. They also correctly noted the ethical lapses in doubling down on AI misuse and the flawed attempt by the attorneys to use ChatGPT to verify ChatGPT’s output. In other words, this post isn’t meant to dunk on AO. But I do want to use this as an opportunity to discuss a fairly recent example of signature blocks mattering.

Lexos V. Overstock (D. Kansas): Six on Signature Block

Signature blocks can be a big deal based on Lexos Media IP, LLC, v. Overstock.com, Inc., (D. Kansas).. See the OSC:

Six attorneys of record appear in this case on behalf of Plaintiff Lexos Media IP, LLC (“Lexos”): five out-of-state attorneys who have been admitted to practice pro hac vice, and one local counsel. On Plaintiff’s recently-filed briefs responding to summary judgment and motions to exclude its experts, the signature pages list five of the six attorneys of record.[Footnote 2]. Yet, only one of Plaintiff’s attorneys—out-of-state counsel Mr. Sandeep Seth—has submitted a declaration admitting to playing a role in submitting the defective citations in Plaintiff’s briefs.[Footnote 3] Overstock filed an opposition to Plaintiff’s motion to correct, noting that counsel’s admitted use of generative AI to draft the brief without confirming the authenticity of the research implicates Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 and Kansas Rule of Professional Conduct 3.3. Overstock has not moved for sanctions on this basis. Nonetheless, the Court may sua sponte “order an attorney, law firm, or party to show cause why conduct specifically described in the order has not violated Rule 11(b).[Footnote4] 'Courts across the country—both within the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit . . . and outside of it—recognize that Rule 11 applies to the use of artificial intelligence.'[Footnote 5, citing Coomer v. Lindell (D. Colorado)].”

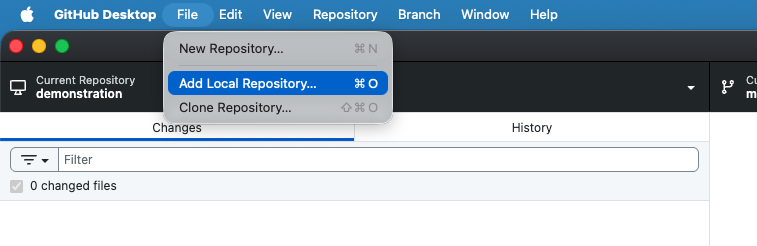

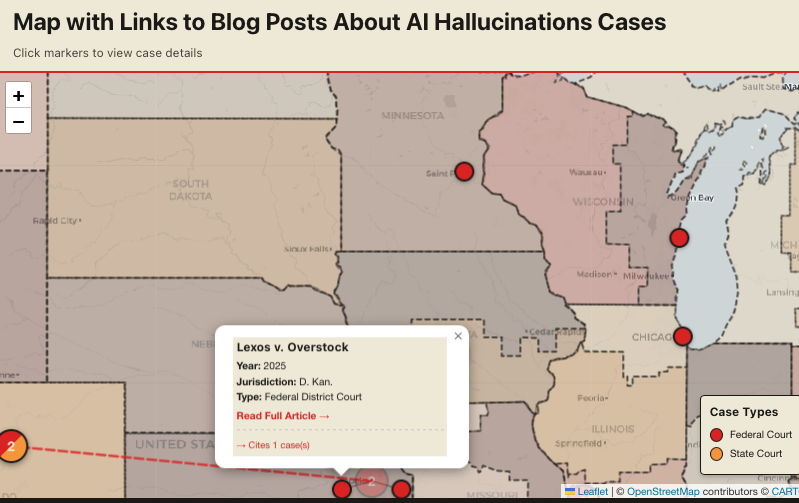

Screenshot of map centered on central U.S., including Colorado, Kansas, and Wisconsin cases.

All Listed Attorneys as Signatories for FRCP 11

Footnote 2 says:

2. While only local counsel’s signature block contains an 's/' before his name, the Court considers all of the listed attorneys as signatories for purposes of Rule 11. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 11(b)(2) (“By presenting to the court a pleading, written motion, or other paper—whether by signing, filing, submitting, or later advocating it—an attorney or unrepresented party certifies that to the best of the person’s knowledge, information, and belief, formed after an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances...the claims, defenses, and other legal contentions are warranted by existing law or by a nonfrivolous argument for extending, modifying, or reversing existing law or for establishing new law.”).

Despite Plaintiff’s motion to correct and Mr. Seth’s declaration eventually submitted along with the reply brief, the Court continues to have serious questions about how the defective citations and quotations in Plaintiff’s briefing came to pass and the role played by the other attorneys who signed these documents on behalf of Lexos, but have not submitted declarations of their own. Accordingly, no later than January 5, 2026, the Court directs each of Plaintiff’s attorneys on the signature blocks of Docs. 193 and 194 to show cause in writing, under penalty of perjury, [emphasis in original] as specified below, why they should not be sanctioned under Rule 11 and referred to the disciplinary panel of this Court and to disciplinary administrators in the jurisdictions where they are licensed.[Footnote 6]

AI Gone Wrong in the Midwest

I am working with a software vendor to get my recorded CLEs available on-demand. This includes “AI Gone Wrong in the Midwest,”, which addresses Pelishek v. City of Sheboygan (E.D. Wisconsin 2025) and Kasten Berry v. Stewart (D. Kansas 2024).

Coomer v Lindell (D. Colorado) case is cited in Lexos v. Overstock as 10th Circuit precedent on AI misuse. The attorneys involved in Coomer v. Lindell later got in trouble again in the 7th Circuit, Eastern District of Wisconsin for more fake citations. That case was Pelishek v. City of Sheboygan (E.D. Wisconsin 2025).

In another D. Kansas AI misuse case, Kasten Berry v. Stewart the judge ordered an attorney from Texas to report for a Wednesday morning Show Cause hearing in person in Kansas.