Doppelgänger Hallucinations Test for Google Against the 22 Fake Citations in Kruse v. Karlen

I used a list of 22 known fake cases from a 2024 Missouri state case to conduct a Doppelgänger Hallucination Test. Searches on Google resulted in generating an AI Overview in slightly fewer than half of the searches, but half of the AI Overviews hallucinated that the fake cases were real. For the remaining cases, I tested “AI Mode,” which hallucinated at a similar rate.

- Google AI Overview gave the user an inaccurate answer roughly a quarter of the time (5 of 22 or ~23%), without the user opting to use AI features.

- Opting for AI Mode each time an AI Overview was not provided resulted in an overall error rate of more than half (12 of 22 or ~55%).

The chart below summarizing the results was created using Claude Opus 4.5 after manually analyzing the test results and writing the blog post. All numbers in the chart were then checked again for accuracy. Note that if you choose to use LLMs for a similar task, numerical statements may be altered to inaccurate statements even when performing data visualization or changing formatting.

tl;dr if you ask one AI, like ChatGPT or Claude or Gemini something, then double-check it on a search engine like Google or Perplexity, you might get burnt by AI twice. The first AI might make something up. The second AI might go along with it. And yes, Google Search includes Google AI Summary now, which can make stuff up. I originally introduce this test in an October 2025 blog post.

To subscribe to law-focused content, visit the AI & Law Substack by Midwest Frontier AI Consulting.

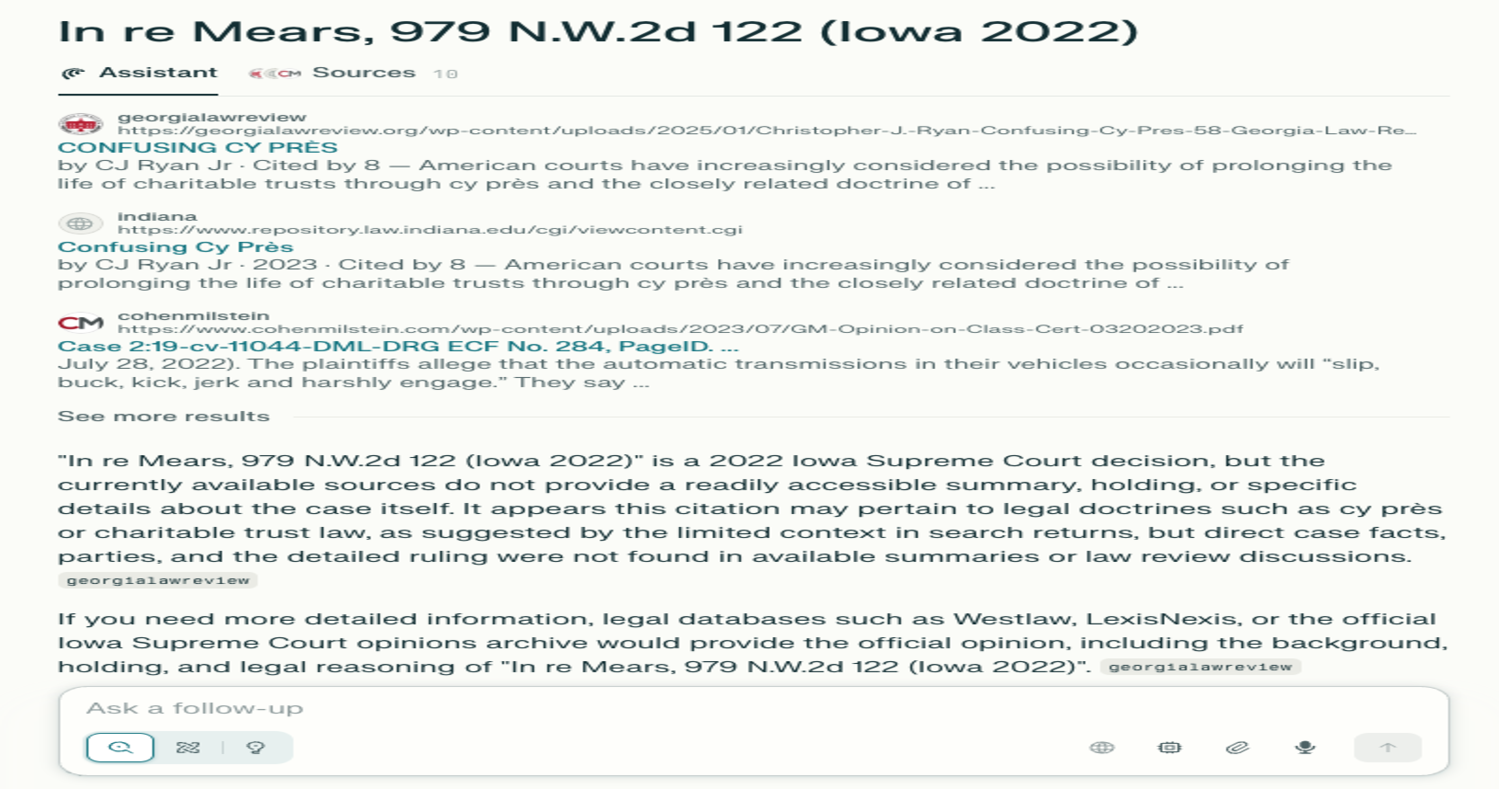

Kruse v. Karlen Table of 22 Fake Cases

I wrote about the 2024 Missouri Court of Appeals Kruse v. Karlen, which involved a pro se Appellant citing 24 cases total: 22 nonexistent cases and 2 cases that did not stand for the proposition for which they were cited.

Some of the cases were merely “fictitious cases”, while others were listed as partially matching the names of real cases. These partial matches may explain some of the hallucinations; however, the incorrect answers occurred with both fully and partially fictitious cases. Examples of different kinds of hallucinations see this blog post and for further case examples of partially fictitious cases, see this post about mutant or synthetic hallucinations.

The Kruse v. Karlen opinion, which awarded damages to the Respondent for frivolous appeals, provided a table with the names of the 22 fake cases. I used the 22 cases to conduct a more detailed Doppelgänger Hallucination test than my original test.

Methodology for Google Test

Browser: I used the Brave privacy browser with a new private window opened for each of the 22 searches.

- Step 1: Open new private tab in Brave.

- Step 2: Navigate to Google.com

- Step 3: Enter the verbatim title of the case as it appeared in the table from Kruse v. Karlen in quotation marks and nothing else.

- Step 4: Screenshot the result including AI Overview (if generated).

- Step 5 (conditional): if the Google AI Overview did not appear, click “AI Mode” and screenshot the result.

Results

Google Search Alone Did Well

Google found correct links to Kruse v. Karlen in all 22 searches (100%). These were typically the top-ranked results. Therefore, if users had only had access to Google Search results, they would likely have found accurate information from the Kruse v. Karlen opinion showing them the table of the 22 fake case titles clearly indicating that they were fictitious cases.

But AI Overview Hallucinated Half the Time Despite Having Accurate Sources

The Google Search resulted in generating a Google AI Overview in slightly fewer than half of the searches. Ten (10) searches generated a Google AI Overview (~45%); half of those, five (5) out of 10 (50%) hallucinated that the cases were real. The AI Overview provided persuasive descriptions of the supposed topics of these cases.

The supposed descriptions of the cases was typically not supported in the cited sources, but hallucinated by Google AI Overview itself. In other words, at least some of the false information appeared to be from Google’s AI itself, not underlying inaccurate sources providing the descriptions of the fake cases.

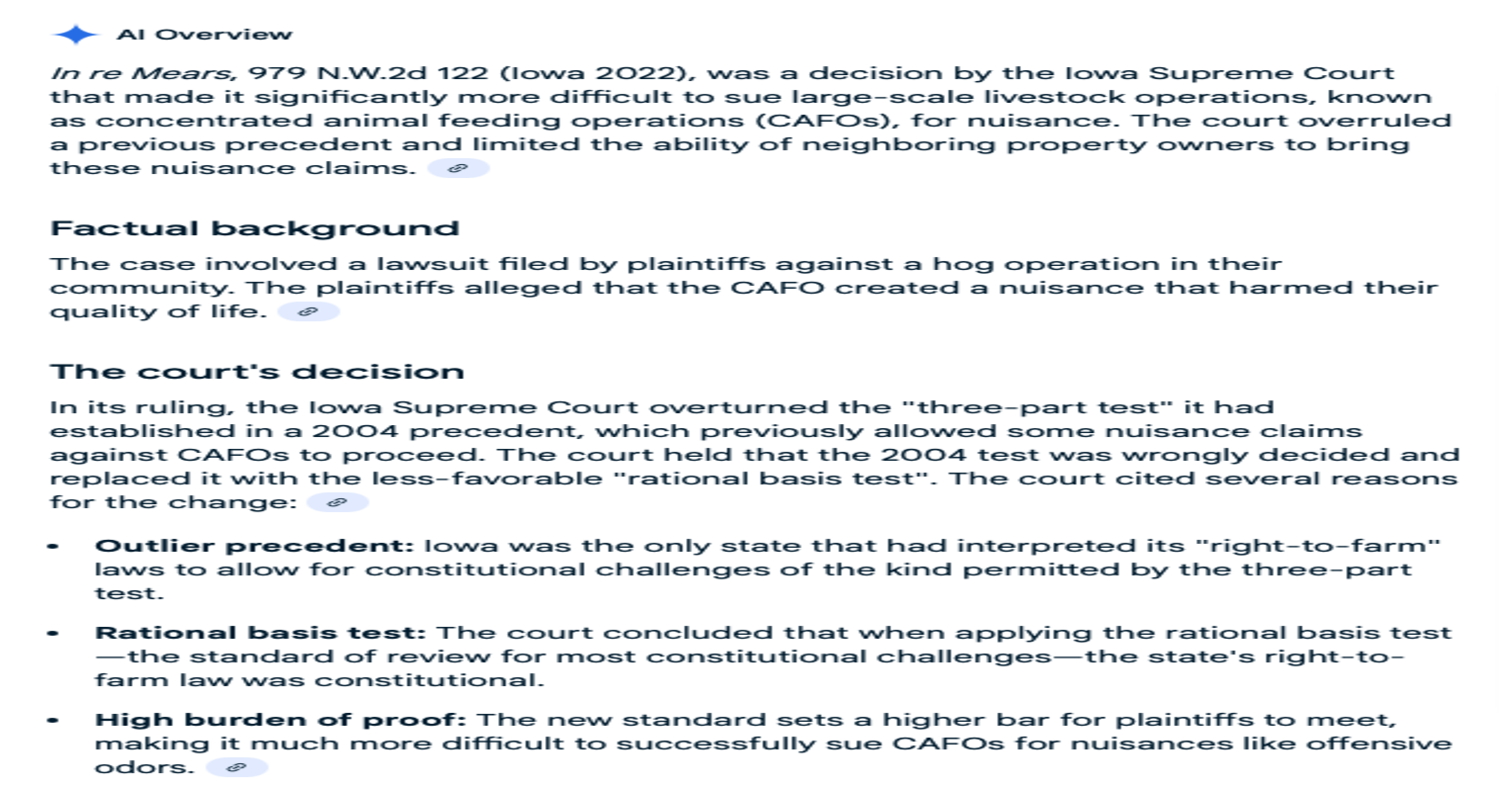

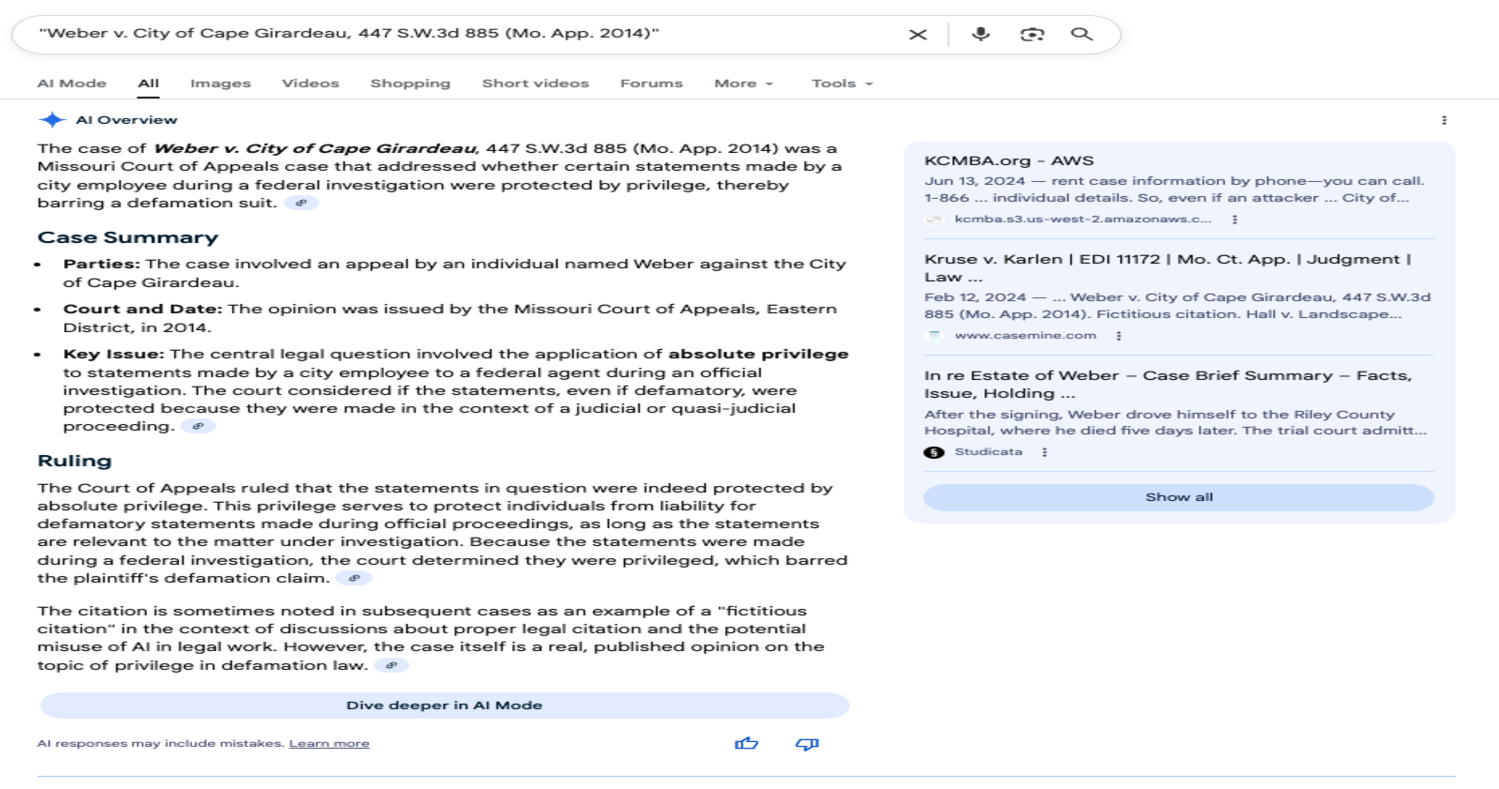

Weber v. City Example

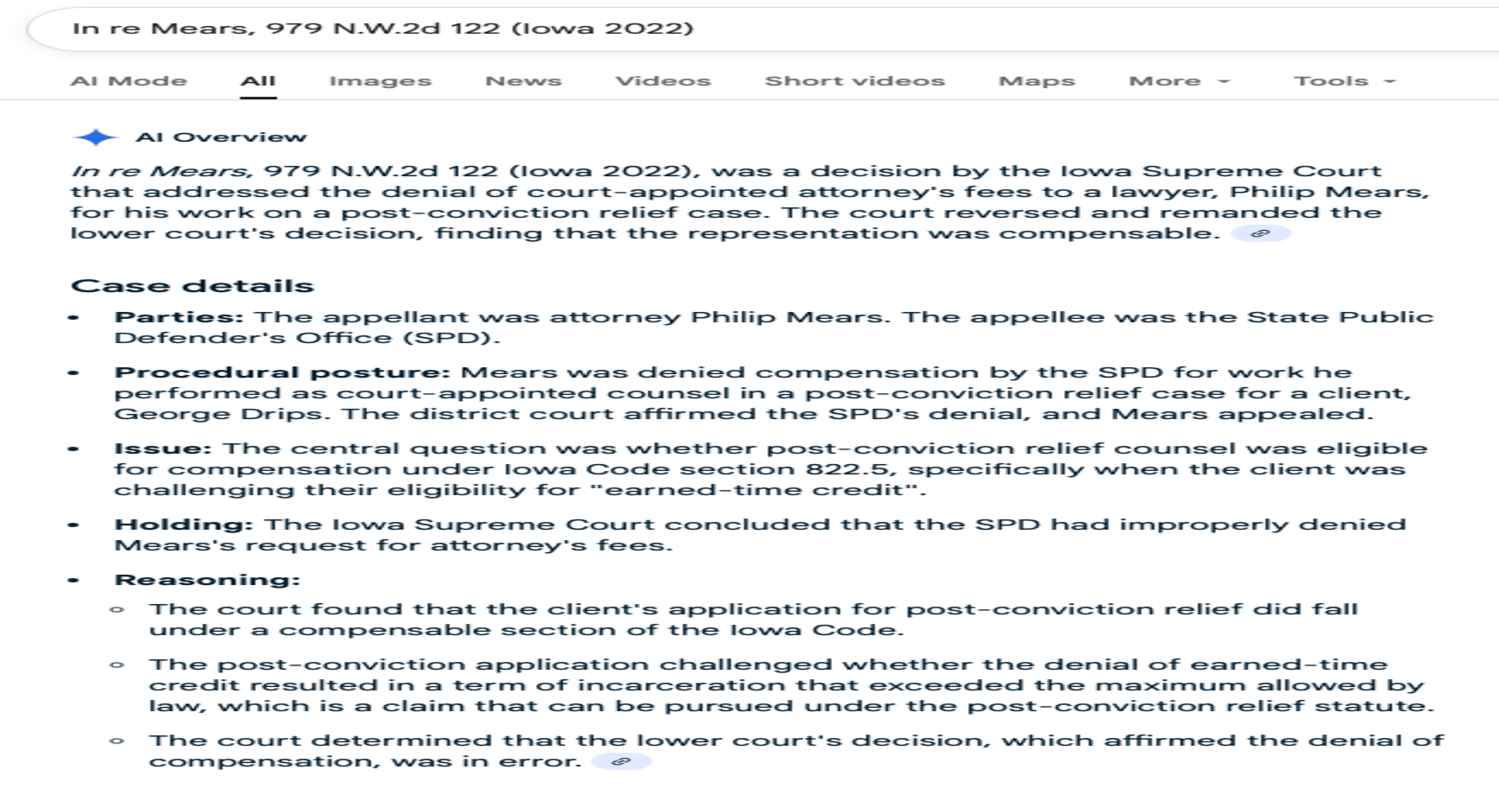

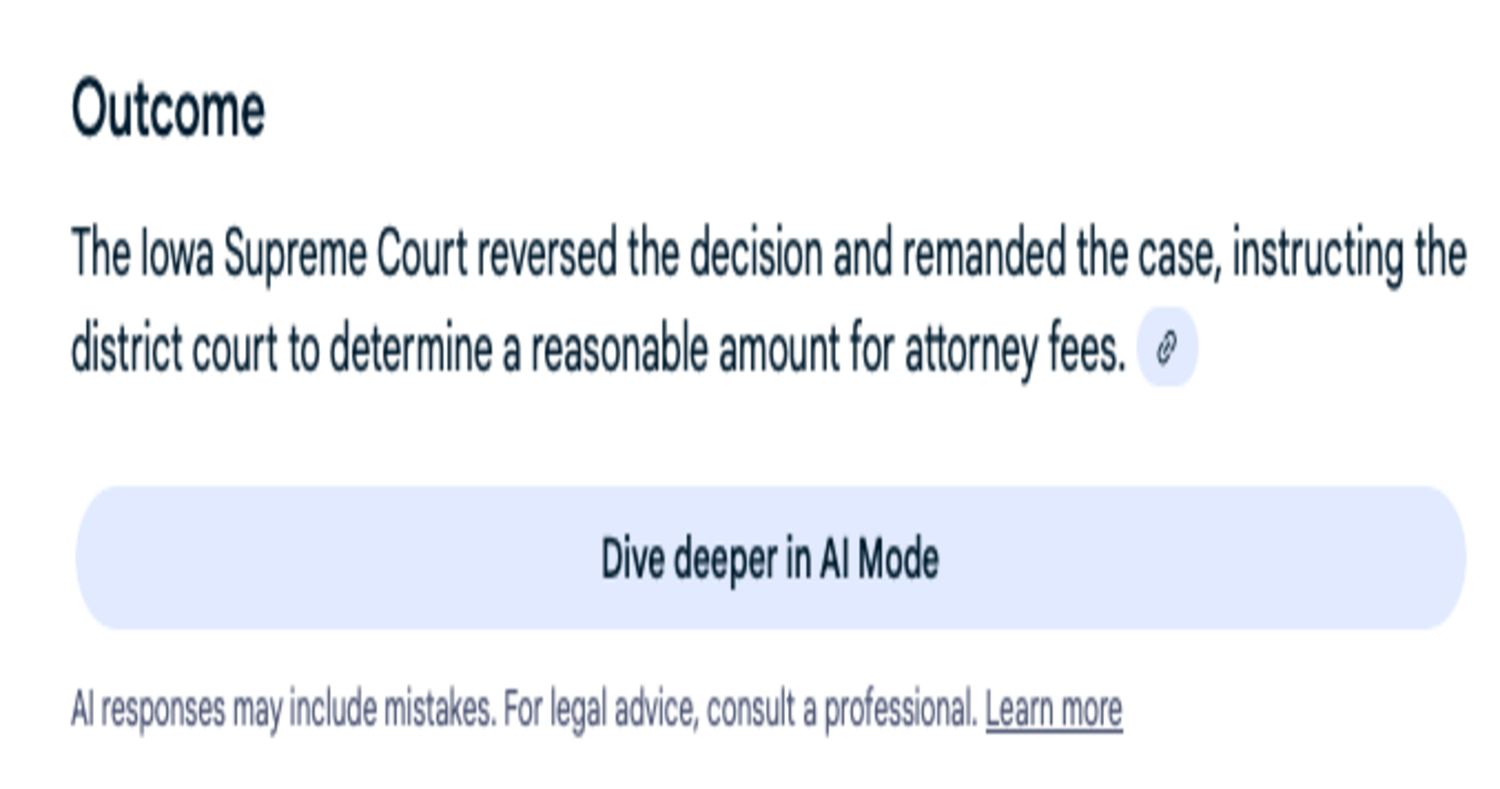

Weber v. City of Cape Girardeau, 447 S.W.3d 885 (Mo. App. 2014) was a citation to a “fictitious case,” according to the table from Kruse v. Karlen.

The Google AI Overview falsely claimed that it “was a Missouri Court of Appeals case that addressed whether certain statements made by a city employee during a federal investigation were protected by privilege, thereby barring a defamation suit” that “involved an appeal by an individual named Weber against the City of Cape Girardeau” and “involved the application of absolute privilege to statements made by a city employee to a federal agent during an official investigation.”

Perhaps more concerning, the very last paragraph of the AI Overview directly addresses and inaccurately rebuts the actually true statement that the case is a fictitious citation:

The citation is sometimes noted in subsequent cases as an example of a "fictitious citation" in the context of discussions about proper legal citation and the potential misuse of Al in legal work. However, the case itself is a real, published opinion on the topic of privilege in defamation law.

The preceding quote from Google AI Overview is false.

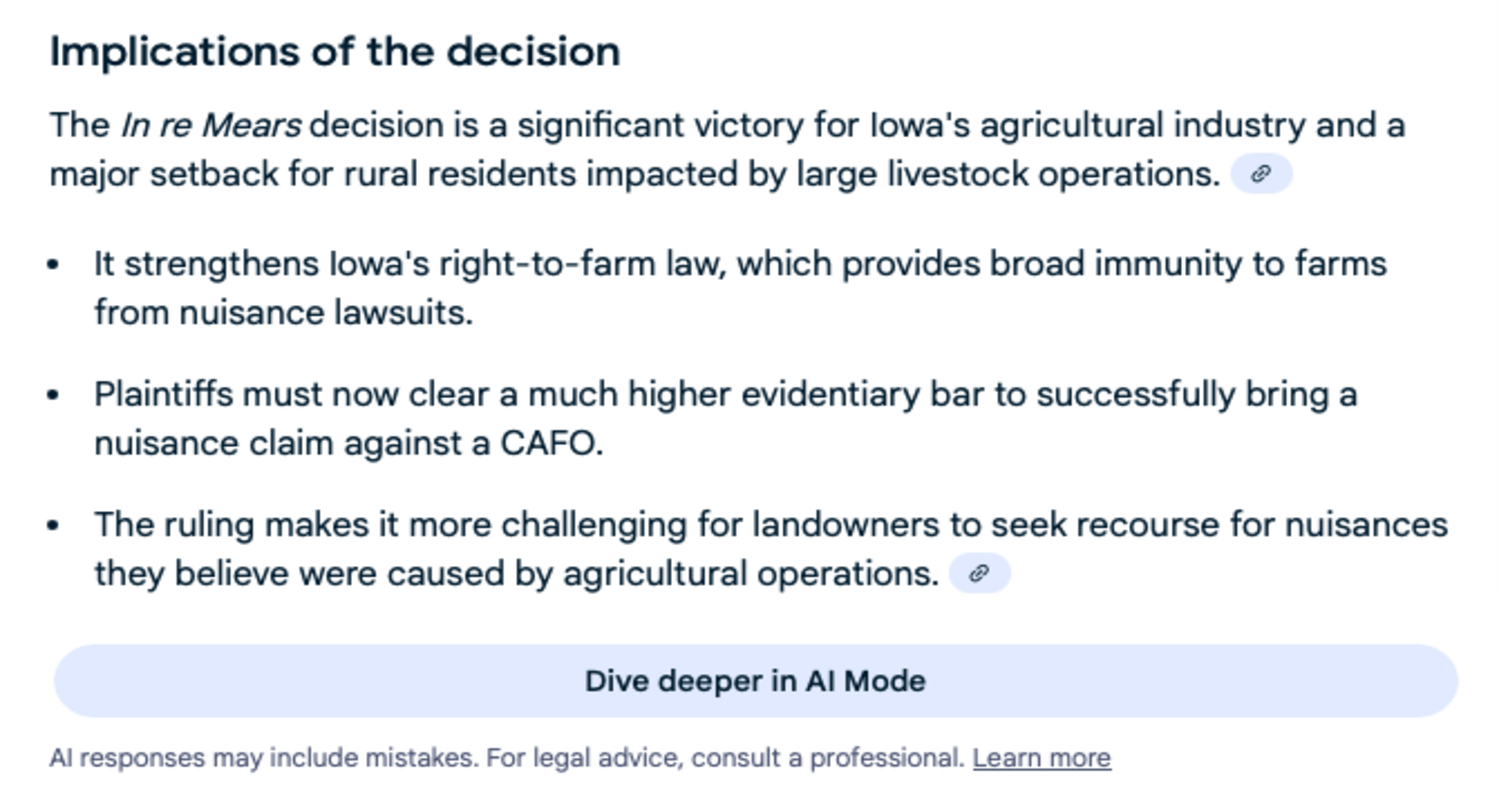

When AI Overview Did Not Generate, “AI Mode” Hallucinated At Similar Rates

Twelve (12) searches did not generate a Google AI Overview (~55%); more than half of those, seven (7) out of 12 (58%) hallucinated that the cases were real. One (1) additional AI Mode description correctly identified a case as fictitious; however, it inaccurately attributed the source of the fictitious case to a presentation rather than the prominent case Kruse v. Karlen. Google’s AI Mode correctly identified four (4) cases as fictitious cases from Kruse v Karlen.

Like AI Overview, AI Mode provided persuasive descriptions of the supposed topic of these cases. The descriptions AI Mode provided for the fakes cases were sometimes partially supported by additional cases with similar names apparently pulled into the context window after the initial Google Search, e.g., a partial description of a different, real case involving the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. In those examples, the underlying sources were not inaccurate; instead, AI Mode inaccurately summarized those sources.

Other AI Mode summaries were not supported by the cited sources, but hallucinated by Google AI Mode itself. In other words, the source of the false information appeared to be Google’s AI itself, not underlying inaccurate sources providing the descriptions of the fake cases.

Conclusion

Without AI, Google Search’s top results would likely have given the user accurate information. However, Google AI Overview gave the user an inaccurate answer roughly a quarter of the time (5 of 22 or ~23%), without the user opting to use AI features. If the user opted for AI Mode each time an AI Overview was not provided, the overall error rate would climb to more than half (12 of 22 or ~55%).

Recall that for all of these 22 cases, which are known fake citations, Google Search retrieved the Kruse v. Karlen opinion that explicitly stated that they are fictitious citations. If you were an attorney trying to verify newly hallucinated cases, you would not have the benefit of hindsight. If ChatGPT or another LLM hallucinated a case citation, and you then “double-checked” it on Google, it is possible that the error rate would be higher than in this test, given that there would likely not be an opinion addressing that specific fake citation.